(Note: Marsha Ward has been writing so long and gave me so much material in my interview that I’ve decided to divide her interview into two parts. This first part will focus more on her newly released book, her writing process, and ANWA.)

Marsha Ward is an award-winning poet, writer and editor whose published work includes four novels in The Owen Family Saga: The Man From Shenandoah, Ride to Raton, Trail of Storms, and Spinster’s Folly. I’ve read and thoroughly enjoyed the first three and am now excited to read the fourth. She’s also written over 900 articles, columns, poems and short stories, given numerous writing workshop presentations, and taught writing.

Here is her description of SPINSTER’S FOLLY:

Marie Owen yearns for a loving husband, but Colorado Territory is long on rough characters and short on fitting suitors, so a future of spinsterhood seems more likely than wedded bliss. Her best friend says cowboy Bill Henry is a likely candidate, but Marie knows her class-conscious father would not allow such a pairing. When she challenges her father to find her a suitable husband before she becomes a spinster, he arranges a match with a neighbor’s son. Then Marie discovers Tom Morgan would be an unloving, abusive mate and his mother holds a grudge against the Owen family. Marie’s mounting despair at the prospect of being trapped in such a dismal marriage drives her into the arms of a sweet-talking predator, landing her in unimaginable dangers.

Me: Is SPINSTER’S FOLLY the conclusion of the Owen Family Saga, or do you foresee more tales? Which of the four books was the most difficult to write, and why?

Marsha: No, the Owen Family Saga continues, with a fifth book to write that already has a title: Gone for a Soldier. I’ll go back into the Civil War to recount the experiences of the oldest son, Rulon. I’m in the preliminary research phase, getting the overview firmly in mind. Later, as I write, I’ll do research for the smaller details, as needed.

Each of the novels have had their unique difficulties in the writing , but perhaps RIDE TO RATON was the most difficult because of scenes at the end. The original final scene contained a lot of vengeful action, which had a negative energy that enfolded me for several weeks. I was angry all the time. I was treating my husband and children like dirt. I didn’t like myself one little bit. It took me a while, but finally it dawned on me that the cause of my ill temper was the bad spirit with which I had ended the novel. That brought me up short and taught me a lesson. I learned words have power.

If I, the author, was having such a bad time dealing with the aftermath of the book, how was it going to impact my readers?

I decided I didn’t want to be responsible for someone wreaking havoc upon those around him or her due to my book. I changed the ending, and made the book much stronger, I think, and leached out the bad taste in my mouth.

The novel still contains the haunting events that precipitated the prior vengeful action, but now the reader weeps at the end instead of wanting to kill someone. I’m satisfied with that.

(Interesting . . . that has been my favorite one so far.)

Me: You’ve had to deal with both loss and health challenges in your life. Which took the greater toll on your writing, and what did you do to overcome it?

Marsha: When my daughter was killed in an auto accident, it sucked the creativity out of me for a number of years. I was so thoroughly immersed in grief and mother-guilt (how had I not kept this from happening to my child?), that I was quite the zombie. I think I finally dealt with the problem when I was invited to join a particular writers’ group and was encouraged to get on with life. Although it came from outside myself, I’m pretty sure those people saved my sanity.

(I find it’s true that no one understands a writer quite so well as other writers. A group is essential.)

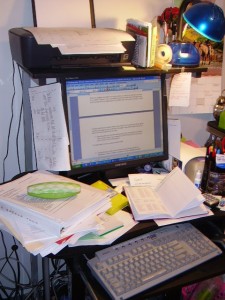

Me: Please describe your favorite writing space in the vernacular of my favorite Owen brother, James, the protagonist in RIDE TO RATON. (And I must have a picture of your writing area.)

Marsha: You really want to see my computer desk? AWK! Oh well. Here’s James to describe it:

“This dear lady, who contemplated upon us Owen brothers for several long years before she gave us life, asked my oldest brother Rulon to call her ‘Mom.’ That don’t set right with me, somehow. It rolls brittle off the tongue. There’s precious little affection in the sound. Kind of hollow. I reckon I’ll call her Abuela. That’s akin to the Southern-style Meemah, or Grandma, but spoke in the Spanish lingo of my first wife, Amparo. She’s…gone now.”

I pat James on the shoulder and step back to wait for him to continue.

“Be that as it may, Abuela has this black piece of furniture sittin’ in a room of her house. It’s not wood, yet it’s not the ‘plastic’ I see about, either. She told me it’s a ‘black laminate wrapped around manufactured wood.’ What the tarnation that means, I cannot fathom. The surface of that there laminate is sort of gritty-lookin’, yet it’s smooth enough to the touch. Cool. Not warm like wood can be. There’s a shelf-like slab that pulls out and holds a sure-enough plastic contraption with letters and numbers and other geegaws that she depresses rapidly to make letters appear on a bright-colored picture frame that sits atop what she calls ‘the desk.’ (Love this!)

“Hush! It don’t look like any desk I ever saw, I tell you. This one don’t have the hidey-holes and whatnots that hide behind the rolltop. Instead, it’s got that picture frame that glows. Yep, I’m not lyin’. It glows with light, just as if it had a lamp behind to shine through a pane of obscure glass. Abuela says it’s called a ‘monitor.’

“The only Monitor I ever heard tell of was the ironclad ship the Yanks sent out to do battle against the C.S.S. Virginia in Hampton Roads in ’62. But that’s another story. I’ve been bid to tell about Abuela’s writin’ area, so I’d best continue that task.

“Abuela tend toward bein’ the untidy sort. I don’t hold it against her. She’s quite a woman. However, the top of her desk is piled with the oddest sorts of things you ever did see. There’s a yellow box sort of thing that has a flap hidin’ an assortment of stiff white cards she writes notes on. Somethin’ she calls passwords. And log-ins.

“I know about passwords from serving in the army during the past troubles. If you didn’t know the proper one for that day, you was like to get shot by the sentry. I can’t make out the meaning of “log-ins.” You could burn up the cards, but they wouldn’t last long enough to give heat nor light like a real log would do. (LOL…yes, our modern vernacular would certainly confuse those who lived 150 years ago.)

“I dassen’t touch the papers and folders she has on one side of that monitor, for fear they’ll tumble off onto the floor. On the other side, she has an assortment of pens made of that plastic stuff, a letter opener, scissors with red handles—red handles! And bent wires designed to hold stacks of paper together for safekeepin’. There’s a little plastic cylinder she calls “eyedrops,” but it’s not made of glass, nor does it have an eye dropper inside of it. She says she squeezes it and the liquid soothes her eyes.

“Abuela has a passel of papers hangin’ off the sides of her picture frame with “tape,” which appears to be a sticky sort of clear plastic that comes from a roll tucked inside another…plastic container. Whew! This world sure does cotton to plastic.

“That’s about all I can say about Abuela’s writin’ spot. I hope that does the job for her friend.”

(It certainly did, and here’s the picture to prove it!)

Me: Along with your novels, you’ve written hundreds of articles for newspapers. Which is harder, journalism or fiction writing? And why?

Marsha: Interesting question. I suppose I could say one is harder because it takes the other side of the brain, or some such thing, but I don’t think one or the other is a more difficult task. They are merely different. I think a competent writer can accomplish a job of writing in any genre, given the time and training. I know other writers won’t agree, but I think I’ve done enough of both kinds to consider myself a generalist rather than a specialist. Now deadlines. Don’t let me go there! (I hear you. I hate deadlines . . . of the daily variety, that is.)

(I do believe listenin’ to James’s account above has me typing a tad bit like he sounds.) :D

Me: What caused you to create ANWA back in 1986? How has it changed over the years and what do you see in its future?

Marsha: ANWA, or properly, American Night Writers Association (now Inc.), came about because of my need to feel comfortable among other writers. I wanted a place where I could learn the craft without being exposed to crass language or themes, and where I could be nurtured rather than batting my head against protective sorts who viewed me as competition instead of offering to share what they knew. I tried out several groups, but soon outgrew the pat-you-on-the-back-and-say-it’s-wonderful clubs. I needed to be challenged, and I wasn’t finding a place where I could grow.

When I came across five other LDS (Mormon) women in a short period of time, each of whom had writing aspirations, I wrote down their contact information and went on my way. One day I was impressed that I had at hand what I needed. I only had to get us together. I called the other five and set up a meeting, and that was the beginning of ANWA.

The organization has gone through many phases. Lean times, when it almost died. Thrilling times, when we had a member put together a workshop that was the genesis of our writers conferences and another begin a website. Growth exploded because of that. We started chapters outside of Arizona and changed our original name of Arizona Night Writers to American Night Writers Association.

After many years of shepherding ANWA and doing a ton of work in the background to keep it going, I was tired of being jealous at the success of those I had mentored. I wanted time to write the stories swimming around in my head, and I told God so. He had thrust me into this task, and I wondered if the time would ever come for me to have a chance to see if I was a writer of any substance, or only a writing coach. I know I pleaded with him for a long time, but finally he said the time had come that I could step back. This has not been an easy transition, and it’s still on-going. However, with the help of several very hard-working, inspired leaders and workers, the burden is slowly slipping off my shoulders. It’s a huge relief, and I’m becoming used to the idea that I don’t have to “do it all” anymore. ANWA will continue to grow. It is poised for international growth soon, where it can influence thousands, and hundreds of thousands of LDS women. It can school them that they have a place in this world, where they can share their light with others through the written word. (Amen! And thank you, Marsha.)

Me: Finally, tell us about your writing process and your current (or next) work in progress. Will you continue to self-publish and, if so, why?

Marsha: As I mentioned in passing, after I succeed in launching my current novel, SPINSTER’S FOLLY, I’ll begin work in earnest on GONE FOR A SOLDIER. My somewhat ambitious goal is to write and publish a novel a year from now on. Self, or indie publishing can enable me to do that, where I wouldn’t be able to control such a schedule through traditional publishing. I don’t have time to dilly-dally around, waiting for the traditional lengthy publishing process. I can accomplish the necessary steps, and make a better income for myself, by being an independently-published author.

And we wish her the best of luck! You can buy Marsha’s novels, including her latest, SPINSTER’S FOLLY, on Smashwords or Amazon. And you can learn more about her from her website, her author blog, her character blog, Facebook, or Twitter.

AND…

You can check in again next Wednesday and learn even more about Martha, including details about her childhood and peeks at several old family photos. Here’s a teaser–a very young Marsha:

Originally posted 2012-11-14 06:00:12.